4P Medicine and the Quintuple Aims

The Quintuple Aims

The quintuple aims are a set of five guiding principles for improving health systems. They consist of:

- Improved patient experience

- Better health outcomes

- Lower cost

- Clinician wellbeing

- Health equity

These aims evolved from the triple aims (patient experience, health outcomes, and cost) [1]. A fourth pillar, clinician wellbeing, was added to form the quadruple aims [2]. This recognised that the quality of care being provided is deeply connected to the environment and wellbeing of the staff providing it. By recognising the importance of clinician wellbeing, we can aim to reduce staff burnout, retain talent, and enhance job satisfaction.

The quintuple aims were formed in 2021 when health equity was added as a fifth pillar [3]. It recognises the varying needs across different groups in the population. Various, tailored approaches may be required in delivering healthcare that meets the needs of all these groups.

4P Medicine and the Quintuple Aims

4P medicine looks at a shift from reactive treatment of established disease to providing healthcare that is personalised, preventative, predictive, and participatory. With the rapidly evolving developments in these fields, we can explore ways of delivering this type of care in health systems. In this article, I would like to explore some of the interactions, alignment, and challenges posed by 4P medicine approaches with the quintuple aims and our healthcare systems.

Improved Patient Experience

People are becoming more informed, involved, and empowered in healthcare. The participatory aspect of 4P medicine strengthens this in many ways. By taking steps to enable people to be active participants in their health and providing collaborative as opposed to directive care, we can enhance the patient experience.

Wearables are routinely used to track health metrics and collect continuous streams of data. Devices such as Fitbit are exploring AI health coaches. I already see a number of patients in my clinical practice who have identified abnormalities through smartwatches, such as new diagnoses of atrial fibrillation. This field will expand with remote monitoring via wearables assisting clinicians to monitor patients, such as those being treated for exacerbations of various conditions such as COPD.

The personalised aspects of 4P medicine also promote ways in which we can improve the patient experience. Pharmacogenomics allows personalised advice on pharmaceutical prescribing based on an individual's genetics. In current practice, medication treatment decisions are usually based on national guidelines and population-based studies. We know that patients are recommended treatments based on studies performed at population levels and clinical pathways. A pharmacogenomic profile can provide personalised information to the clinician and patient in order to guide treatment decisions based on whether the patient is likely to be a 'poor' or 'rapid' metaboliser for a number of commonly prescribed medications.

Poor metabolisers take longer to process the medications and are more likely to experience side-effects. This could lead to more dangerous consequences such as toxicity causing harm, additional contacts with the health system, or even hospital admission.

Rapid metabolisers may require higher doses to achieve a therapeutic response to a medication. In these situations, a pharmacogenomics profile may provide useful information highlighting that a higher than usual dose may be required. Without this knowledge, a treatment may be classed as ineffective for an individual when only a low initial dose was used.

The preventative and predictive aspects of 4P medicine are strongly aligned with improving patient experience. These elements focus on maintaining a healthy, independent state, free of disease. By focusing therapeutic interventions, societal support, and healthcare resources to prevent the development of disease, people can live healthier and happier lives. The patient experience is enhanced not just by reducing the suffering caused by disease but by enabling individuals to live more independent and healthy lives.

Better Health Outcomes

We have already explored how technologies such as pharmacogenomics could deliver improved outcomes through avoiding iatrogenic harm from medications. Developments in personalised medications could transform our ability to treat rare and complex diseases, as well as providing novel interventions for conditions that are currently difficult to cure.

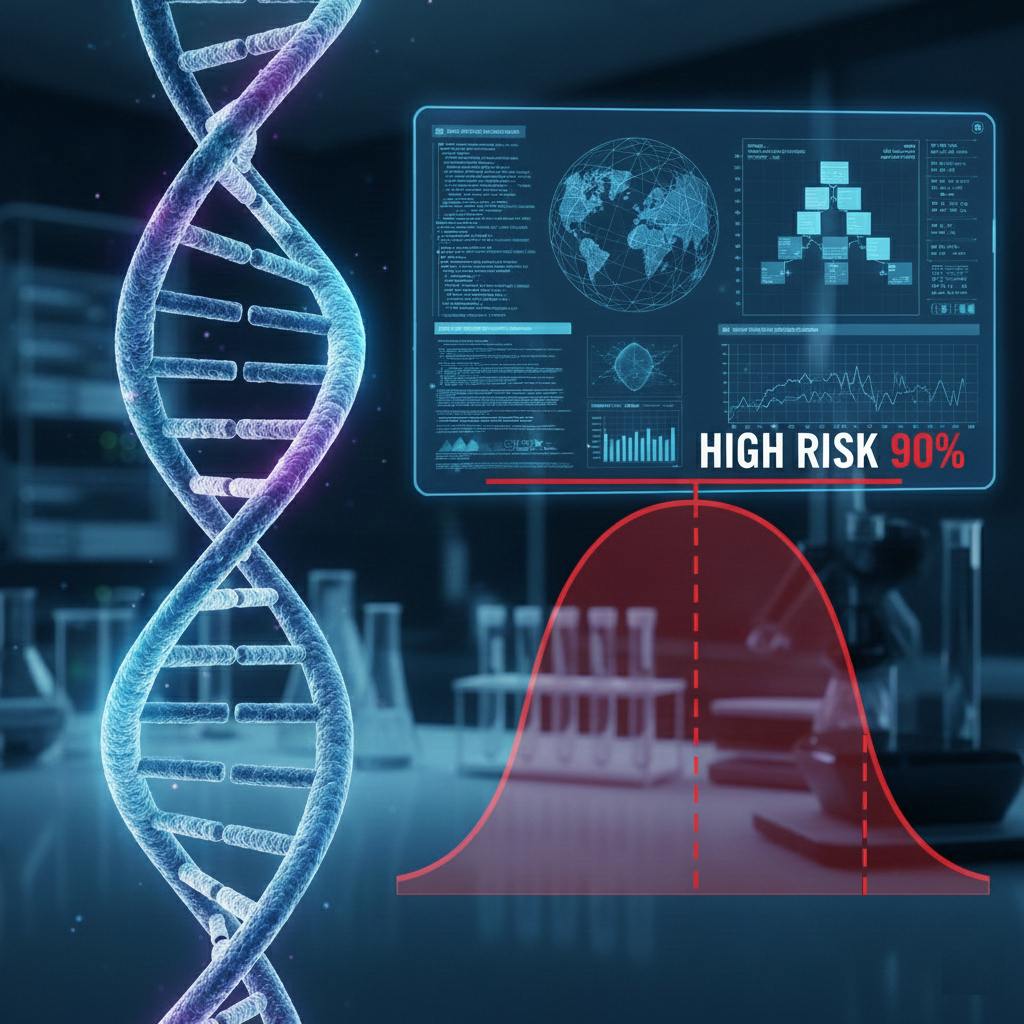

An area that is seeing increasing focus is on polygenic risk scores. The BARCODE1 study looked at identifying men at increased risk of developing prostate cancer using a polygenic risk score [4]. If we look at the men identified as being in the top 10% of genetic risk (polygenic risk score ≥ 90th centile) that went on to have screening, 40% of these men were found to have signs of prostate cancer. Of these cases of prostate cancer, 55.1% of the cancers we seen as clinically significant (Gleason score 3+4) and requiring treatment. Notably, 70.9% of these cancers would have been missed by the standard UK diagnostic pathways for prostate cancer.

There has been very interesting discussion within the community about the interpretation of these results [5]. We have to confirm whether earlier detection of disease actually results in better health outcomes. These technologies have the potential to identify patients who have very early changes that would not have caused any long-term health impacts. Once identified, these patients often undergo investigations, interventions, and treatments that may result in complications and morbidity. Professor Lucassen noted in their response that polygenic risk scores predict occurrence but not aggressiveness of disease, and without evidence that early detection improves outcomes, such approaches risk amplifying overdiagnosis and overtreatment. With any technology looking at identifying diseases at an earlier stage, these aspects need careful consideration to ensure that they genuinely improve rather than negatively impact health outcomes for patients.

Lower Cost

New technologies often have a high initial cost. Pharmacogenomic panels currently cost approximately $250-$500 per test, with basic single-gene tests ranging from $150-$400 and comprehensive panels up to $2,000 [6]; however, the cost is set to reduce with increased laboratory capacity and wider implementation. When considering 4P medicine, there are a number of aspects around cost to consider. If people are spending a higher proportion of time in a healthy, disease-free state through early interventions and preventative health, then the cost burden of chronic disease is reduced. The interventions and support are not without cost, and there is a risk of increasing costs through identifying asymptomatic individuals needing intervention.

One aspect of cost related to 4P medicine is the focus on enabling individuals to maintain a healthy, independent state with a reduced burden of chronic disease. Neurodegenerative diseases such as dementia are set to place an increasing burden on our health and social care systems with an ageing population. In the UK, the cost of dementia was £42 billion in 2024, projected to rise to £90 billion by 2040, with 982,000 people currently living with dementia expected to increase to 1.4 million [7]. If preventative and predictive approaches within 4P medicine can help avoid or prevent the development of these conditions, the total costs could be substantially reduced.

Clinician Wellbeing

When considering clinician wellbeing in the context of 4P medicine, an important aspect is the emotional toll of managing complex, late-stage incurable disease. Healthcare workers do a remarkable job in managing the devastation and human suffering they experience on a frequent basis. This, combined with the strains these issues place on an overburdened healthcare system, can cause stress and burnout in healthcare workers. Many aspects of 4P medicine could improve this in two ways: by addressing the underlying causes and preventing the volume of patients requiring this care within the health system, and through staff providing more aspects of preventative and proactive healthcare, which they may find more professionally fulfilling and less emotionally harmful.

An important aspect of 4P medicine to consider when discussing clinician wellbeing involves the role of the clinician as an interpreter and guide in these conversations. When combining multiple types of data and clinical information for an individual, the clinician will play a vital part in interpreting the results and guiding decisions. These conversations could pose complex scenarios for which there are no single right answers. This uncertainty and complexity could be challenging and may negatively impact clinician wellbeing.

Health Equity

Health equity is an important aim to consider alongside 4P medicine. As new technologies come to the market and interest grows in this field, it is often the group of people who are most technologically and financially able that benefit first. These are often not the same group of people who would benefit the most. There is therefore the potential that the divide could worsen, with 4P medicine becoming a premium tier of care that accelerates a two-track system, with the benefits provided by these advancements flowing to the already advantaged.

Predictive strategies in 4P medicine could allow redirection of care to those who need it most. By reducing the burden of chronic disease on the healthcare system, access to healthcare resources may be improved for all.

We must also consider the sources of the training data used when developing algorithms, genetics, and biomarkers for disease prediction. Prediction models trained on homogeneous populations can perform poorly for underrepresented groups, potentially widening disparities rather than closing them [8, 9, 10].

Conclusion

In summary, there are many aspects of 4P medicine which align well with the quintuple aims. There are also challenges that would need careful consideration when introducing these technologies into healthcare systems. The examples discussed throughout this article demonstrate some of the opportunities and risks. By keeping all five quintuple aims in focus, not just technological innovation, healthcare systems can work towards realising the potential of 4P medicine while ensuring benefits for the whole of the population.

REFERENCE LIST

- Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Affairs. 2008;27(3):759-769. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Annals of Family Medicine. 2014;12(6):573-576. doi:10.1370/afm.1713

- Nundy S, Cooper LA, Mate KS. The quintuple aim for health care improvement: a new imperative to advance health equity. JAMA. 2022;327(6):521-522. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.25181

- McHugh et al. BARCODE1 study. New England Journal of Medicine. 2025;392(14):1406-1417.

- Lucassen et al. BMJ response. BMJ. 2025;389:r1179.

- American Pharmacogenomics Association. How much does a pharmacogenomics test cost? What you need to know before you pay. August 8, 2025.

- Alzheimer's Society & Carnall Farrar. The economic impact of dementia – Module 1: annual costs of dementia. May 2024.

- Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019;366(6447):447-453. doi:10.1126/science.aax2342

- Cross JL, Choma MA, Onofrey JA. Bias in medical AI: implications for clinical decision-making. PLOS Digital Health. 2024;3(11):e0000651. doi:10.1371/journal.pdig.0000651

- Duncan L, Shen H, Gelaye B, et al. Analysis of polygenic risk score usage and performance in diverse human populations. Nature Communications. 2019;10:3328. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-11112-0